Copper transfer plates

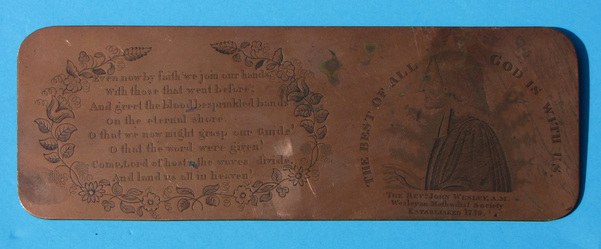

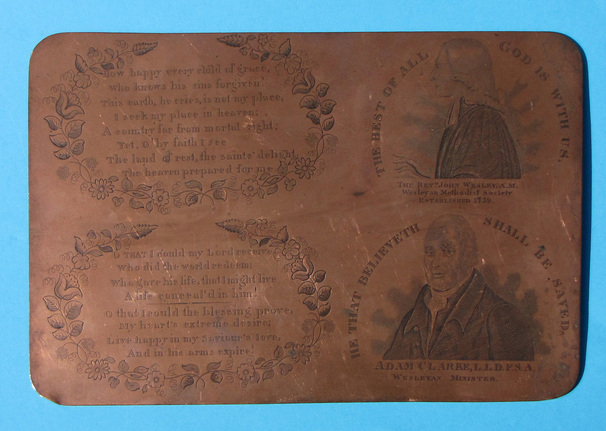

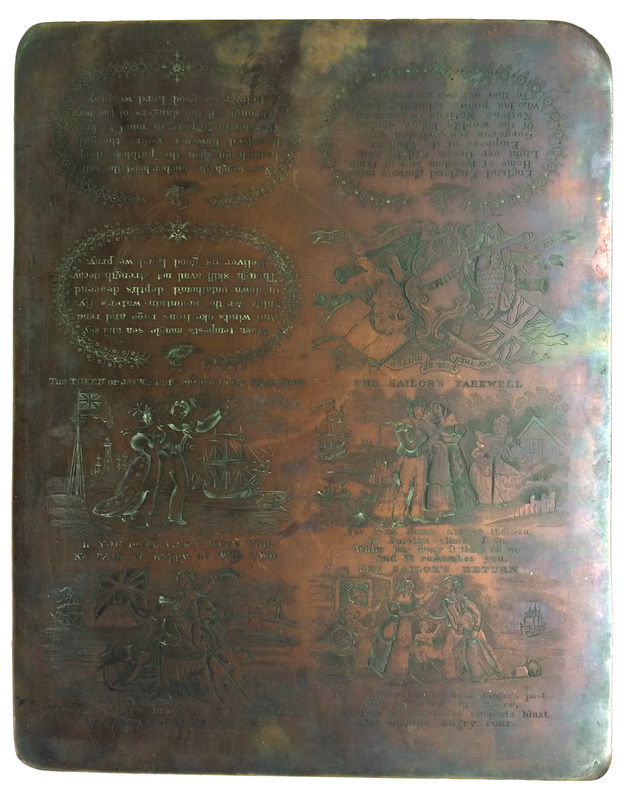

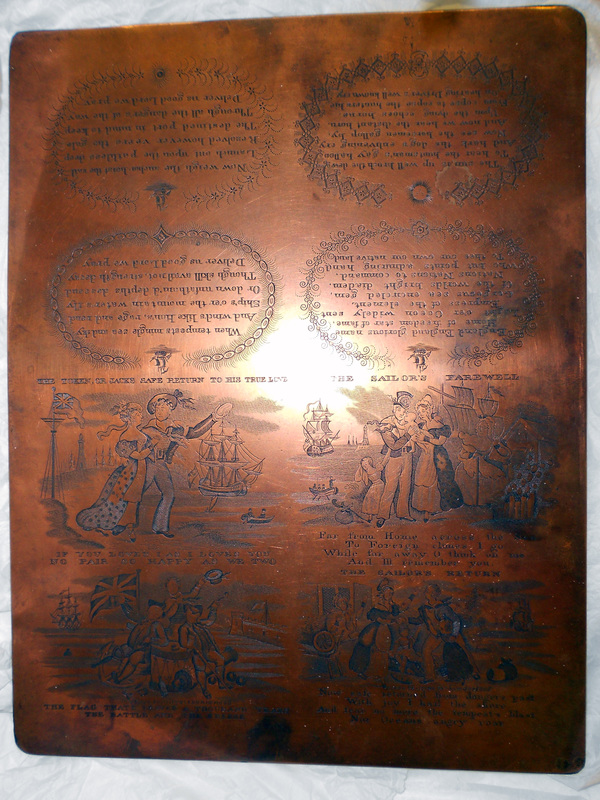

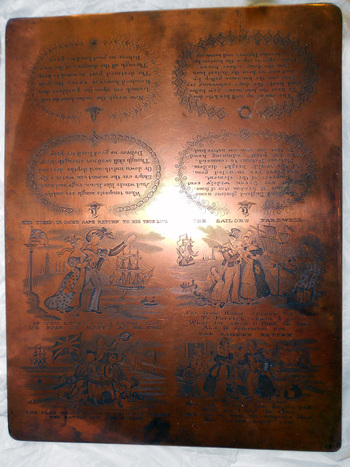

The transfers on pottery come from designs hand-engraved onto copper plates (this one from the collection of Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums). The heated plate was covered with ink, and the excess wiped off. Damp tissue was then laid over the plate, and both were passed through rollers. The plate was put on a hot stove, so that the paper dried and could be removed with the printed image upon it, but in reverse. The paper was then laid over the pottery, and rubbed hard with tools, until the ink on the paper had transferred to the pottery. The pottery was soaked in water so that the paper floated off, leaving the image on the pottery, now the right way around.

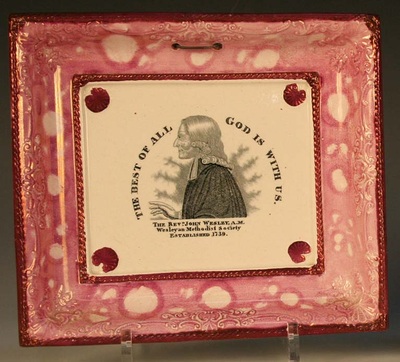

Transfers could either be directly applied to plain earthenware (under-glaze), or on top of a glaze (over-glaze). Under-glaze transfers give a nicer effect, as the ink better grips the pottery body, but it is harder to apply transfers to curved surfaces in this way. So jugs and bowls often have over-glaze transfers, which have a tendency to smudge and distort. Whereas plaques, with their flat surface for printing on, are more often under-glaze.

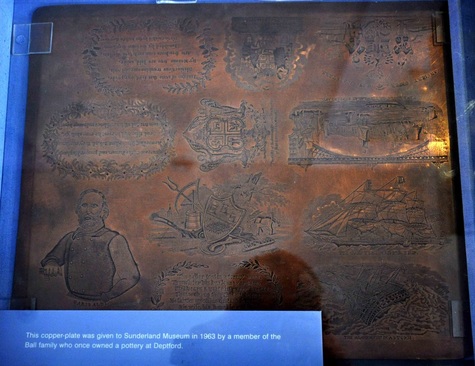

The process of engraving copper plates was highly labour intensive. One shortcut that appears to have been used was for an engraver to transfer print the image of an existing copper plate onto another piece of copper, to engrave a second plate. As a result, some copper plates had images so similar, it is hard to tell their transfers apart. I have, for instance, recorded 5 almost identical variations of the 'Prepare to Meet Thy God' transfer from Sunderland potteries. You can see two almost identical John Wesley images below. These copper plates were donated to John Wesley's Chapel, The New Room, Bristol, by a friend of a descendant of the owners of Ball's Deptford Pottery. Read more about them on the Scott page.

Transfers could either be directly applied to plain earthenware (under-glaze), or on top of a glaze (over-glaze). Under-glaze transfers give a nicer effect, as the ink better grips the pottery body, but it is harder to apply transfers to curved surfaces in this way. So jugs and bowls often have over-glaze transfers, which have a tendency to smudge and distort. Whereas plaques, with their flat surface for printing on, are more often under-glaze.

The process of engraving copper plates was highly labour intensive. One shortcut that appears to have been used was for an engraver to transfer print the image of an existing copper plate onto another piece of copper, to engrave a second plate. As a result, some copper plates had images so similar, it is hard to tell their transfers apart. I have, for instance, recorded 5 almost identical variations of the 'Prepare to Meet Thy God' transfer from Sunderland potteries. You can see two almost identical John Wesley images below. These copper plates were donated to John Wesley's Chapel, The New Room, Bristol, by a friend of a descendant of the owners of Ball's Deptford Pottery. Read more about them on the Scott page.

The Wesley transfer plates were likely engraved in the 1830s, for Scott's Southwick Pottery. They were used until 1897 and beyond, when they were acquired by Ball's. The left plaque below is from the 1830s, the centre plaque likely from the 1860s, and the last plaque, attributed to Ball's, from the 1890s. The copper plates were very valuable (see here), so when a business folded, it was not uncommon for them to be sold on and for their use to continue elsewhere. The quality of the imprint from the plates deteriorated over time.

The deterioration of the plates - scratches and nicks in the copper - sometimes help us to trace the movement of a specific copper plate from one pottery to another. The plates, after being passed through rollers many times, had a tendency to bow, and occasionally needed to be flattened out. The engraved grooves which held the ink flattened and become more shallow over time, so the imprints became greyer and less well defined. Sometimes the plates were re-engraved to restore the clarity of the image.

Sadly, very few of these copper plates survive. If you know the whereabouts of any others used on North Eastern pottery, please get in touch. To read more about the two copper plates below click here and here.

If you wish to see a copper transfer plate in the flesh, there's one in the Sunderland Museum. It's in an unmarked pull-out drawer under one of the displays. The plate, from c1860, contains an assortment of largely unrelated transfers, which helps explain the apparently random pairings you find on some objects. This one was used by Scott's on plaques and bowls, and then passed on to Ball's whose descendants donated it to the museum. The Garrison Pottery had a very similar transfer plate (read more here).