|

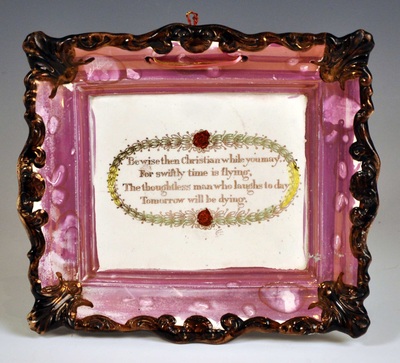

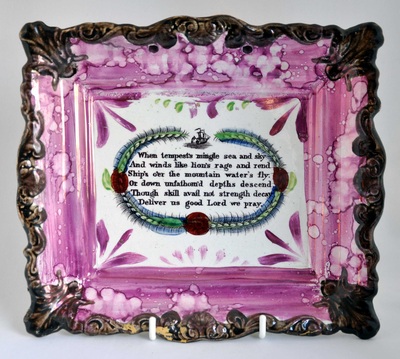

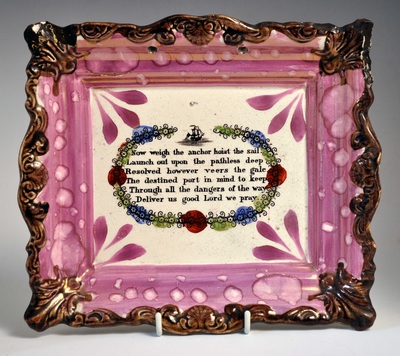

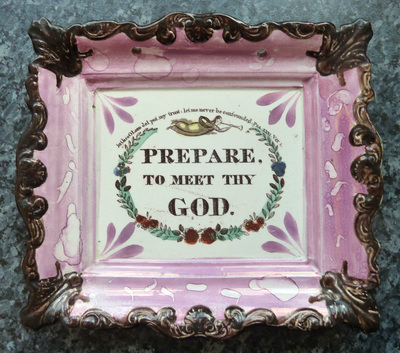

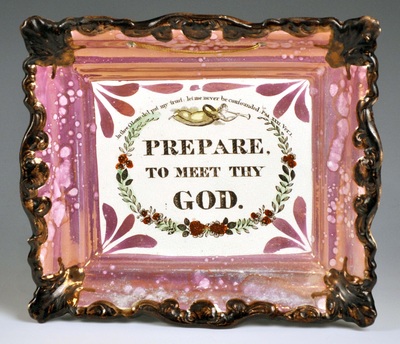

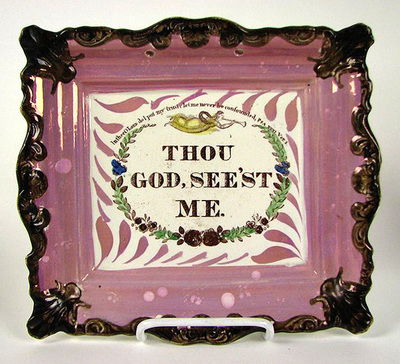

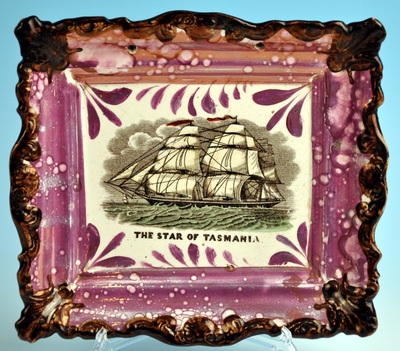

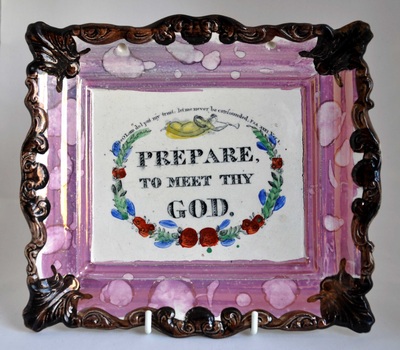

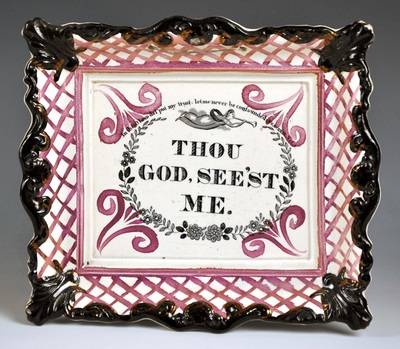

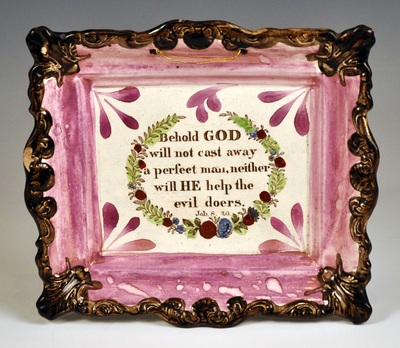

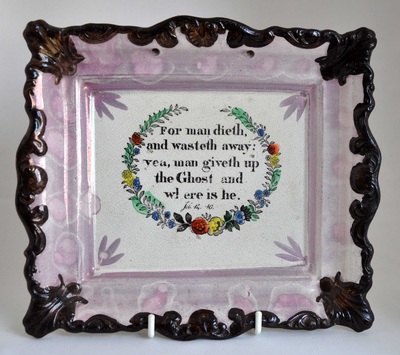

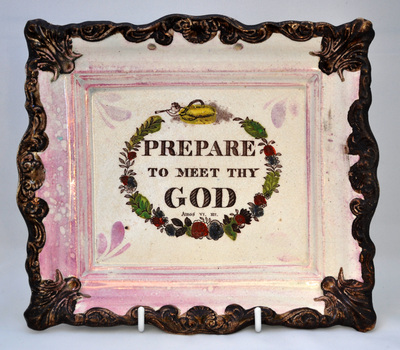

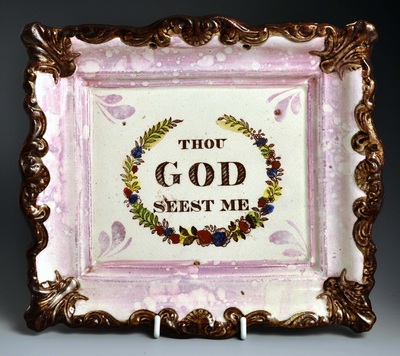

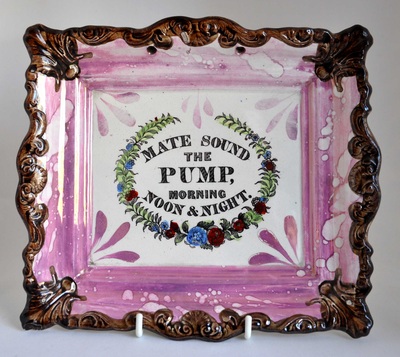

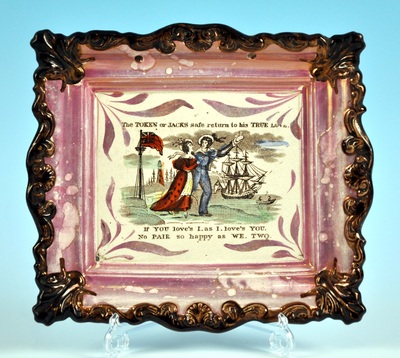

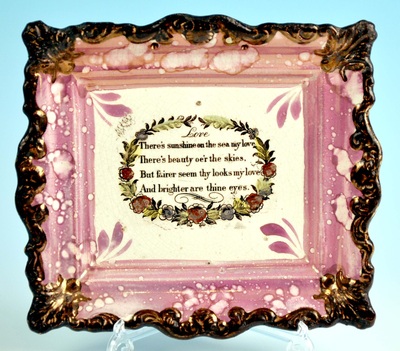

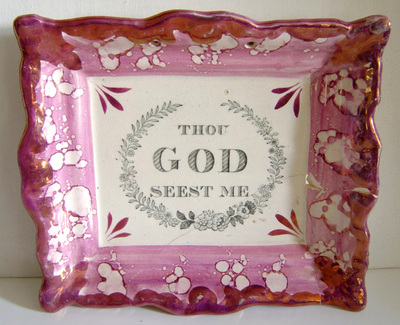

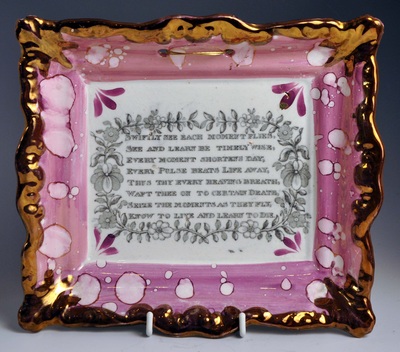

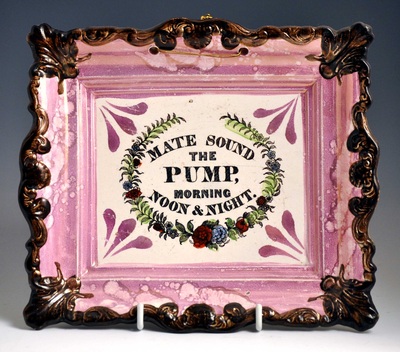

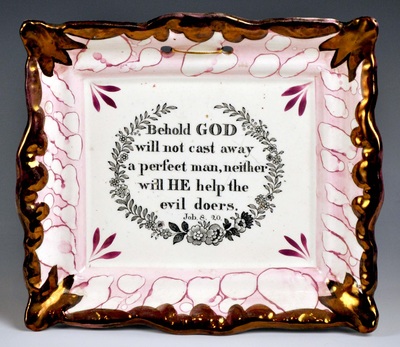

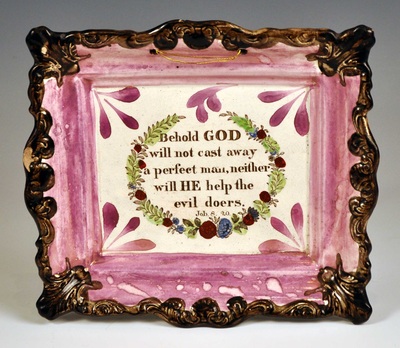

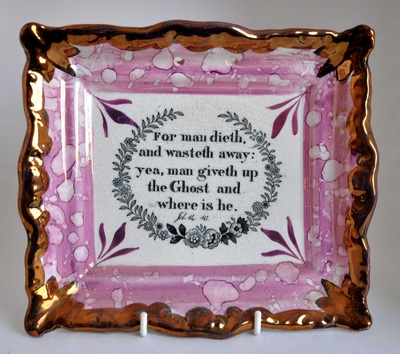

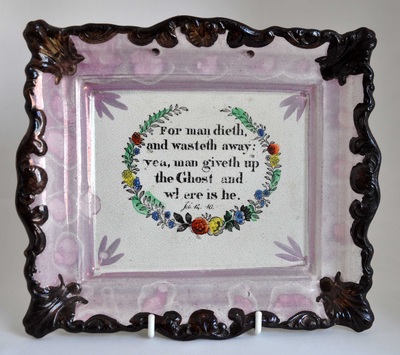

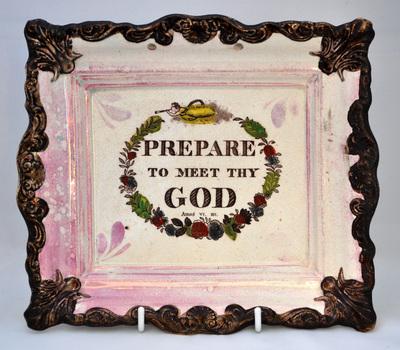

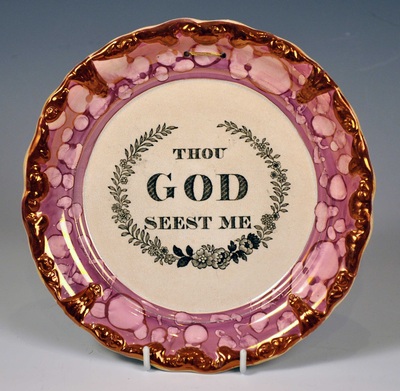

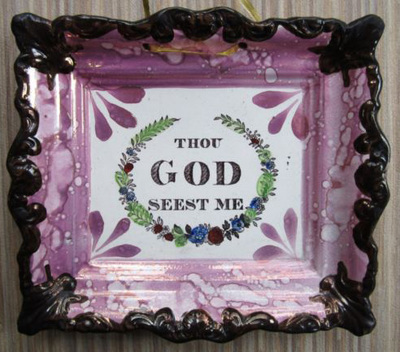

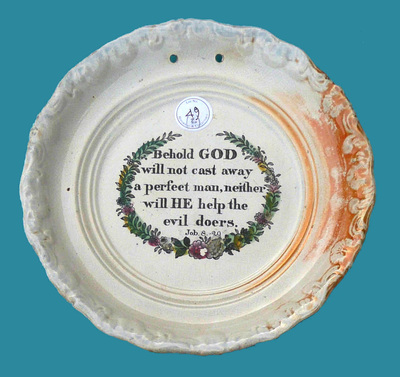

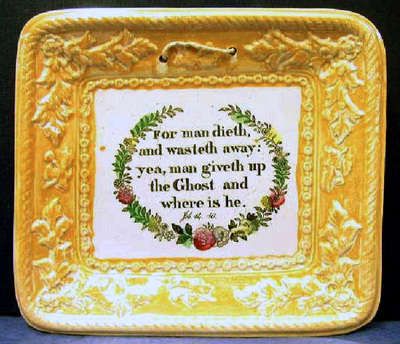

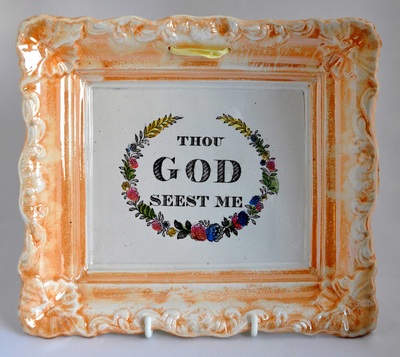

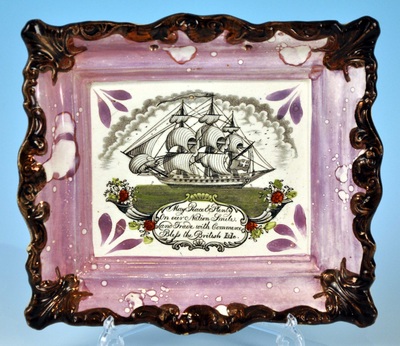

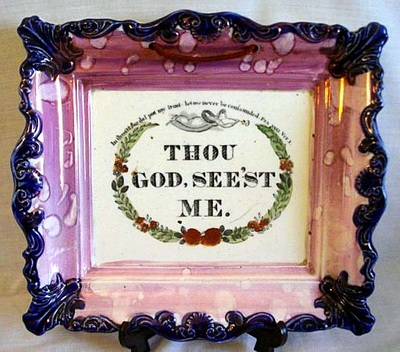

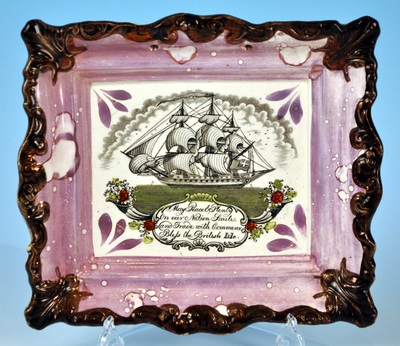

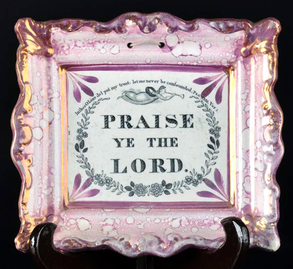

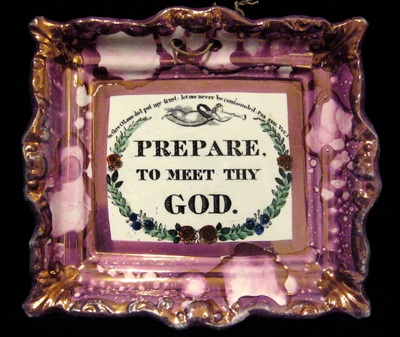

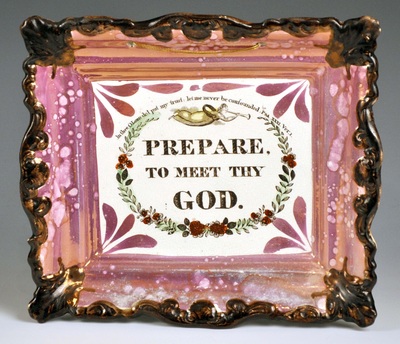

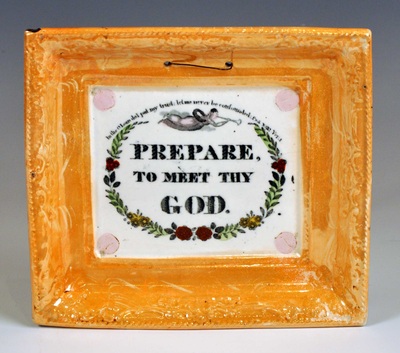

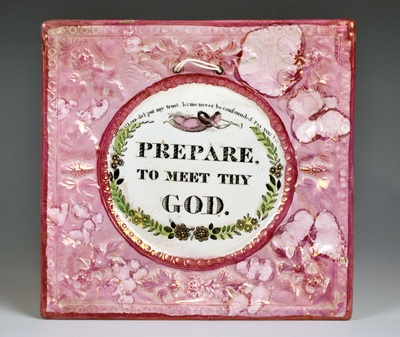

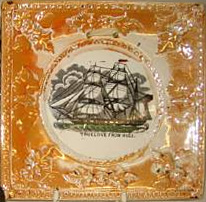

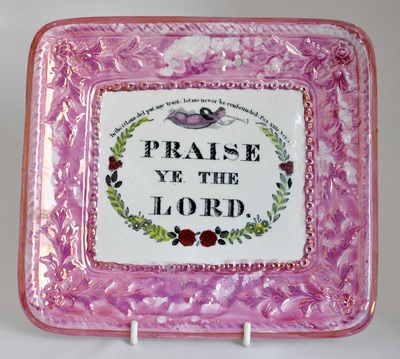

If you've visited this post before, you'll see I've been refining it over the last few days. There are at least 47 different transfers that appear on brown-bordered plaques. Few collectors will manage to get even a full set of ships, of which there are at least 12 (13 counting 'May Peace and Plenty'). Each of the photos in this post represents a different transfer. So where did the transfer plates come from? Transfers from MooreThe largest group of transfers I can trace back to an 1850s' source come from Moore's (21 of the 47 transfers in this post). I have earlier Moore-impressed plaques with the first two transfers below. The next three also appear on typical Moore plaques from the 1850s. The 'Frigate in full sail' transfer (last plaque below) hasn't yet been recorded on a Moore plaque. However, it does appear on a Moore-marked bowl dated 1859. The first and second transfers below appear on the Moore-impressed bowl dated 1859 (see above), so although they don't appear on Moore plaques, I've included them in this section. The third plaque pairs with the second, so I've included it also. Four different common verse transfers on brown-bordered plaques can be traced back to Moore. Below are two 'Prepare' transfers - one from Sunderland plate 4 and one from plate 5 - and a 'Thou God' and 'Praise Ye' from Sunderland plate 4. (For an explanation of the numbering of the different plates, see the 'Religious' verse pages.) The transfers below have all been recorded on items from Moore's in the 1850s. One is so rare that I don't yet have images of the brown-bordered version (top right). Transfers from ScottIn truth, we can't be certain that any of the transfers that appear on brown-bordered plaques came from Scott. The Scott group 1 transfers never appear on this plaque form. There's as yet no firm evidence that the transfers in Scott group 2 come from Scott, as they don't appear on identifiable Scott wares. The supposition that the transfers came from Scott's is entirely based on working backwards from these brown-bordered plaques, which are widely attributed to that pottery. Although the transfers in this group are few in number, the May Peace and Plenty is the most common of all the brown-bordered ship plaques. There are three verse transfers from this group that make it onto the brown-bordered plaques. The first is from the Sunderland plate 2 'Prepare' transfer plate. The second from the Sunderland plate 3 'Thou God' transfer plate. The third is from the Sunderland plate 3 'Praise' transfer plate. Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest the second and third transfers originated at Newbottle, which had links with both Scott and Moore. The verse transfers below are much more common on brown-bordered plaques than the Moore versions above. The transfer plates in this group all appear to have been retired (probably from over use) before the orange lustre period. Transfers from DixonThese were discussed at length in my previous post, but here they are again. As I've already set out, I believe Moore is the strongest contender to have purchased these transfers. Transfers of unknown sourceThe transfers below haven't as yet been recorded on earlier Scott-attributed or Moore-marked items. I think there's a reasonable chance that the first three, at least, will be found one day on Moore-marked items from the 1850s. It's not surprising that the second group below haven't been recorded on earlier items. The Great Australia transfer is after an engraving in the Illustrated London News from 1860. The Unfortunate London didn't sink until 1866. That transfer is so rare on brown-bordered plaques that I don't have a photo of one (I don't yet have a photo of a brown-bordered Mariners' Arms either, so have included an orange version). My guess is that the plaques below (with very similar decoration) have transfers which debuted on the brown-bordered plaques after 1865. They all appear relatively commonly on orange-lustre jugs and bowls from the 1870s. Their later date explains why they appear so rarely on brown-bordered plaques: they were produced over a much shorter period, i.e. just before orange lustre superseded the plaques with brown borders. So what's to be concluded from all this? There was perhaps a little more innovation regarding transfers during this period than I had given credit for. But still the majority of transfers were recycled (33 vs 14), and some of the first group in the last section were copies of other potteries' transfers.

By far the largest contributor of recycled plates was Moore: triple the number that came from Scott (21 vs 7, or 26 vs 7 if you include the Dixon transfers). And there's some doubt whether the 7 transfers I've attributed to Scott did indeed come from that pottery. Why not Newbottle? There is homogeneity of decoration across all the groups above (I have livened things up by including less typically decorated items). You'll see where I'm going with this. There's little reason to suspect that these plaques were decorated at multiple locations. And if they were decorated at one location, surely Moore is our front runner.

1 Comment

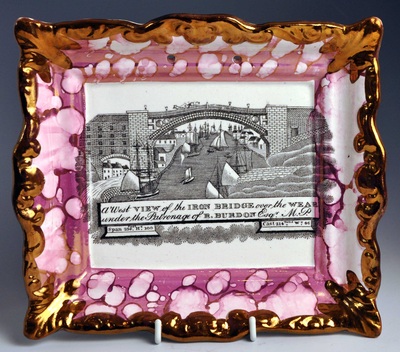

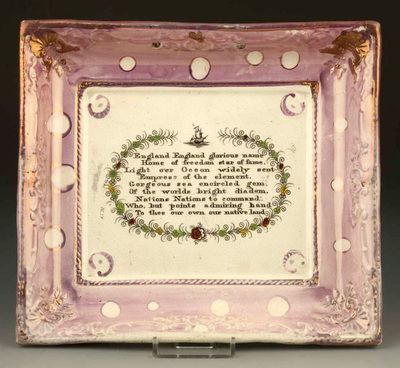

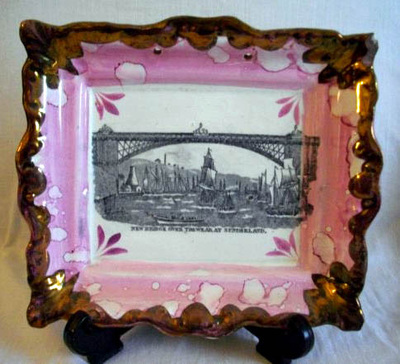

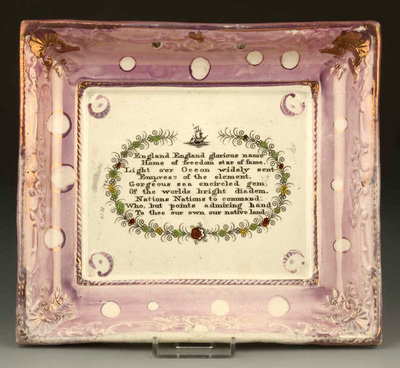

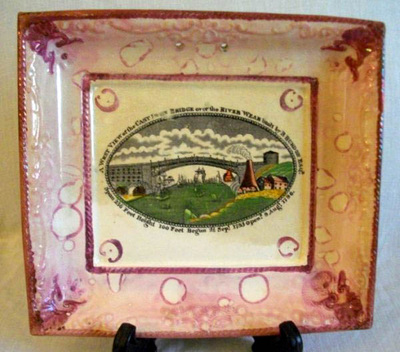

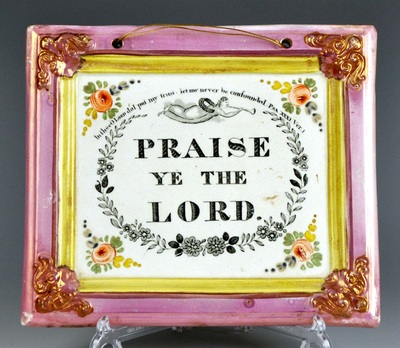

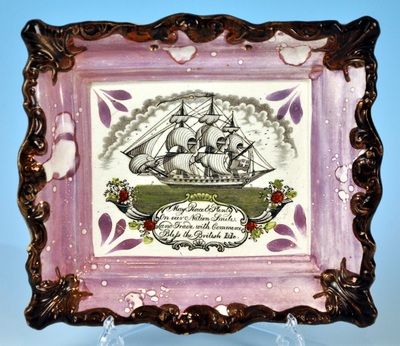

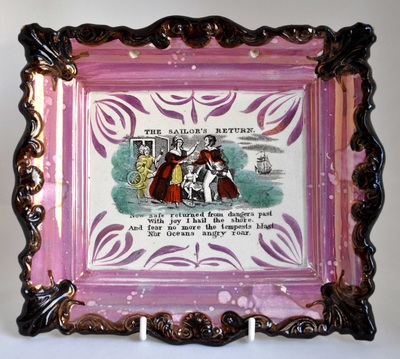

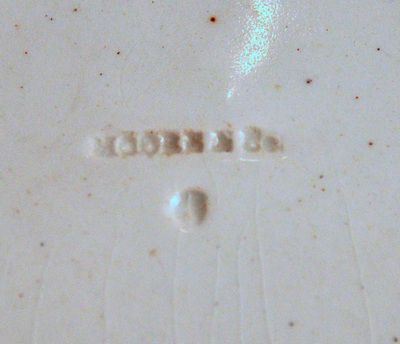

6/28/2014 0 Comments Dixon's demiseThe Garrison Pottery's closure in 1865 is helpful for dating plaques. That year, the transfer plates were sold, likely at auction, along with Dixon's other effects. So any non-Dixon plaque, with a Garrison transfer, has to have been made after that date. Baker references a transfer plate, presented by a member of the Ball family to the Sunderland Museum, that appears to have 'passed into the hands of either Moore's or Scott's (possibly both) and finally to Ball Brothers'. The selling and recycling of transfer plates is perhaps in itself significant. Aside from the Newbottle verse transfers, I can't think off hand of other transfer plates moving from pottery to pottery on Wearside before 1865. Recycling of transfers seems to happen largely in the later period, and fits with a more cost-conscious, less inventive, approach to turning out pottery. At its height, Dixon's made fabulous quality lustreware (see below left). But by the 1860s, quality had deteriorated (centre and right) with heavy potting and degraded transfers. Even so, the transfer plates still had value, and were sold on to other potteries for reuse. Transfers that went to CarrJohn Carr & Sons, of North Shields on Tyneside, bought a quantity of Dixon transfer plates (see below, Dixon plaques left, and Carr right). Carr appears to have had the transfer plates heavily re-engraved, but mitigates that with exuberant 'clobbering' (enamel decoration) and lustre flourishes. There is another verse, 'Friendship, Love and Truth', that went from Dixon to Carr, but I don't yet have a photo of a Dixon example. It's likely that the Dixon 'May Peace and Plenty' also went to Carr (see last two plaques below), but there are minor differences between the transfers, which might be down to re-engraving. Transfers that went to ScottThe transfer plates that went to Scott and appear on the group 1 plaque form (see my last-but-one post) are fairly limited. The Sailor's Return and 'England, England' verse (first two plaques below) are two of the transfers listed by Baker as appearing on the Dixon transfer plate at the Sunderland Museum. There are 7 transfers on this one copper plate, so there are potentially 5 more variations of these rare plaques yet to be recorded (more on that, hopefully, in another post sometime). The Gauntlet Clipper Ship (Dixon version, top right) appears very rarely on the Scott group 1 plaque form (bottom left) from the 1860s. If Scott was making brown-bordered plaques at this time, why isn't the transfer found on them? It would fit very naturally in the ship group. It isn't until the orange-lustre period that the Gauntlet joins them, on the plaque form with rounded corners, also attributed to Scott (last two plaques). As discussed in my last-but-one post, the view of the New Bridge over the River Wear first appears on Dixon items (top left below), and then on the Scott group 1 plaque form (top centre and right). The transfers also pair on a jug (bottom left and centre), with very similar decoration to the Scott-attributed Farmers' Arms jug mentioned in a previous post (bottom right). There may be other transfers from Dixon that make it onto the Scott group 1 plaque form. For instance, the transfer 'Agamemnon in a Storm' frequently appears with the Gauntlet on Dixon items, and it is likely that both transfers were engraved on the same copper plate. Transfers that appear on brown-bordered plaquesLet's start with the transfer that gave the name to this website. A circular Dixon (c1860) version is shown on the left, beside a typical brown-bordered plaque (post 1865). Whoever made the brown-bordered plaques (whether Scott or Moore) clearly had an interest in purchasing the common verses from Dixon. Although the brown-bordered plaques (right examples below) were made in large numbers, there are more Dixon versions (left examples) with these transfers. N.B. the Dixon plaques are the output of much longer period: 1840-1865. The motivation for purchasing the transfer plates must have been to squeeze the last drops of commercial value from four of Dixon's top sellers. It appears to have been a canny move, as the popularity of these transfers continued into the 1870s and the orange-lustre period. Incidentally, Dixon didn't have a 'Praise Ye the Lord' transfer, so whoever produced the brown-bordered plaques appears to have had one made to complete the set (bottom left). The bottom centre plaque has a hand-painted date '1875', which helps us fairly accurately date these orange plaques. The first, circular, plaque below is of a typical Moore form. The second is the round-cornered form attributed to Scott. It is only during this orange-lustre period that there's a complete mixing of transfers on Scott and Moore forms. This ties in nicely with Norman Lowe's theory that at some point both potteries were sending their wares to the same place - Sheepfolds Warehouse - for decoration. So who made the brown-bordered plaques? You'll probably have guessed that I think this inches us a little further towards Moore. Even amongst the transfer plates purchased from Dixon, there appear to be two distinct groups. The transfers that appear on Scott group 1 items have never yet been recorded on brown-bordered plaques. What better explanation for this than they were made at two separate locations? It is only in the orange-lustre period that the transfers are used on Scott and Moore plaque forms interchangeably. Interestingly, there is no orange-lustre version of the brown-bordered plaque form.

6/22/2014 0 Comments More on the ship transfersFirst of all, thanks to Ian Holmes and Norman Lowe for their suggestions and photos. I've been thinking again about the transition between the golden age of transfer-printed plaques of the 1840s and 50s, to the mass-production era of the 1860s and beyond. It's not a perfect analogy, but think about the way that novels are published. When a book is new and in vogue, it is released in a hardback edition of a few thousand: expensive to print, with a quality binding, which the publisher can charge a premium for. The market for hardbacks is relatively small, so when the initial excitement surrounding the book is over, it has to compete in a mass market, and the publisher releases it as a cheap paperback in editions of tens or even hundreds of thousands. Now think about the Moore ship plaques of the 1850s: topical, lightly potted, carefully decorated, produced in small numbers... You get the picture. A similar shift in strategy might explain why there are so many more brown-bordered ship plaques than early Moore-impressed examples. By the 1860s pink lustre was becoming old fashioned - it had been around for decades. There was stiff price competition from the more technologically advanced Staffordshire potteries. The advancement of railway networks meant that Staffordshire factories could compete in the same local market. It's no coincidence that around this time (1865) the Garrison Pottery folded after a long period of decline. The Galloway and Atkinson partnership, at the Albion Pottery on Tyneside, barely lasted a year (1864). It was a hard time for North Eastern potters. Baker reports that Moore's too, after a change of ownership in 1861, had to reinvent itself. A manager called Ralph Seddon from Staffordshire was appointed, and 'on his advice the works were largely rebuilt and equipped with modern machinery'. Between 1866 and 1872 the pottery was reported to be the largest on Wearside. Operating at full capacity, Moore's could have employed up to 250 hands, although was reported to have 180 during this period, whereas Scott's employed about 150 (Baker). It was during Moore's period of expansion that the brown-bordered plaques were made in huge numbers. So why is generally assumed they were made by Scott? Isn't it equally possible that the ship plaques continued to be made by Moore? The main argument against this is that the transfers frequently appear on Scott bowls and jugs. But as I never tire of repeating, records show that Scott supplied Moore with plain earthenware for decoration (I've asked the Sunderland Museum if these records are dated, but as yet have not heard anything). The other argument is that the 1860s' brown-bordered plaques look nothing like marked Moore plaques. The late brown-bordered plaques (below right) do, however, have a more than passing resemblance to earlier plaques attributed to Scott (below left). The earlier plaques are, however, slightly smaller and more finely potted. The plaque below, recently listed on eBay, changed the way I'd been thinking. So what's so special about it? Well firstly, the transfer originated around 1847, and belongs to the groups of Moore transfers listed in my last-but-one blog post. Secondly, it has a printed Moore mark (below right). Thirdly, it has copper lustre borders - almost brown - rather than the pink borders we'd generally associate with Moore. Fourthly, the lustre is a deep purple, like that found on the brown-bordered plaques. It appears to be, however, from the standard Moore rectangular mould (smaller than the brown-bordered plaques). I think this is a game changer, and shows that Moore could just have easily made the brown-bordered plaques as Scott. It is the nearest thing we have to a marked prototype. Incidentally, Ian Holmes points out that he also has a Moore Bottle plaque with copper lustre borders and purple lustre (below). I also remembered on Ian Sharp's site, a plaque with unusual blue borders attributed by him to Moore. Ian notes that the 'Success to the Fleece' transfer appears on earlier Moore items. I would have loved to have found an image of one, but the best I could come up with was the bowl below right, which the auction catalogue describes as 'signed Moore & Co, verses including Success to the Fleece and Waverley designs'. You can just make out the edge of the transfer to the right of the photo (click to enlarge). This is important in as much as the 'Fleece' transfer, like The Bottle above, appears to have been used exclusively by Moore. The plaque below is apparently from the same mould as the ship plaques with brown borders. But let's not get too carried away by the idea that blue borders always come with Moore transfers. Ian Holmes has two plaques with similar blue borders. The left plaque below has the Moore & Co 'Praise Ye' (plate 4) transfer, but the right plaque has the Scott-attributed (plate 3) transfer. Incidentally, the brown-bordered plaques would have started with a blue edges like this. When the pink lustre is painted over them, the blue turns to copper. You can see this in the centre detail above. Although the plaques below aren't a true pair, it is hard to imagine that they weren't decorated at the same location. So where does this leave us in terms of the ship transfers? I set out three possibilities at the end of my last-but-one post, that sometime around 1860 either:

The ship transfer plates moved to Scott This is possible, but I haven't found any real evidence for it yet. If Scott held the transfer plates, what was Moore's part in this division of labour? There's no record I'm aware of that Moore sent earthenware to Scott for decoration; records show movement of pottery in the other direction. But, to throw in a cliche, perhaps there's no smoke without fire. The received wisdom that Scott made the brown-bordered ship plaques must have some basis in fact for the idea to have established such a strong hold. The pottery was big enough to have produced plaques in large numbers, and also went through a period of modernisation (although it is less clear from Baker when). Moore decorated plain earthenware for Scott with ship transfers This seems logical at present. But a clearer idea of the dates that Scott supplied Moore with earthenware would need to be established. We know that by the mid 1860s, Moore's was the larger pottery, so we might expect it to have had the additional capacity to cope with decorating Scott's wares. The plaques above show that Moore was decorating objects in similar style to the brown-bordered plaques as early as the 1850s. And, looking back at the late group 1 'Scott' transfers in my previous post, the plaques that Scott appears to have been making in the 1860s were of a higher quality than the brown-bordered plaques. Although it is possible that Scott made both quality wares and cheaper wares to feed two different markets (this might account for why the transfer plates of the two groups remained separate). The ship transfer plates moved to Sheepfolds, who decorated wares for both Moore and Scott with ship transfers, while turning out glass rolling pins on the side This is Norman Lowe's theory, and why not? We know that Sheepfolds made glass rolling pins, and there are plentiful examples of glass rolling pins with the ship transfers. However, some of the other transfers that appear on the rolling pins, 'Love and be happy' for instance, are more closely associated with the orange-lustre period of the 1870s. I think that Sheepfolds is a strong contender to have decorated the later, orange ship plaques from both Moore and Scott. But as for the brown-bordered plaques of the 1860s, I'm not so sure. So as ever there's no clear answer. A wider study of Scott- and Moore-marked wares might add to the debate. P.S.Look at the corner details of the three plaques below. The 1850s' Scott-attributed plaque (left) has a transfer that also appears on brown-bordered ship plaques (right). However, the plaque with a Moore printed mark (centre) has an almost identical corner detail to the brown-bordered plaque. Below is another transitional item with a Moore plaque form, transfer, and typical pink lustre borders, but with the three lustre strokes in each corner around the transfer that often appear on later brown-bordered plaques. All this got me thinking. What if the plaques with Sunderland plate 5 'Prepare' transfers were all Moore? The plaques below would nicely demonstrate the transition of decoration, from the pink lustre of the 1850s, through purple lustre, to the brown-bordered plaque of the 1860s. Perhaps the watchword should be, 'Render unto Moore the things that are Moore's, and unto Scott the things that are Scott's'.

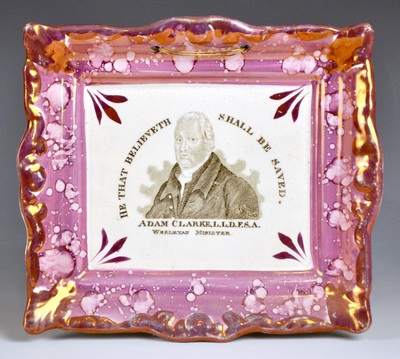

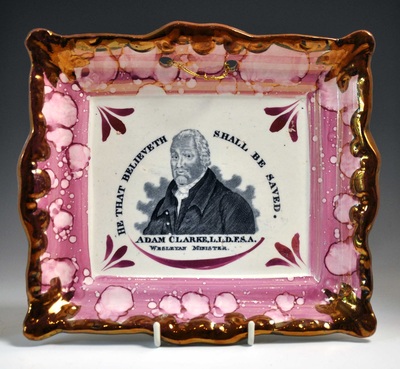

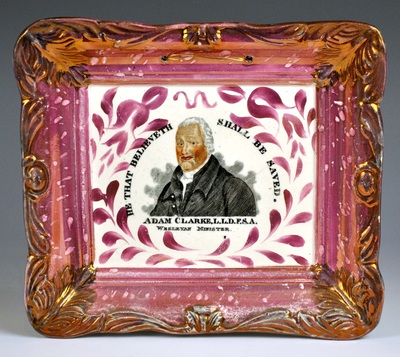

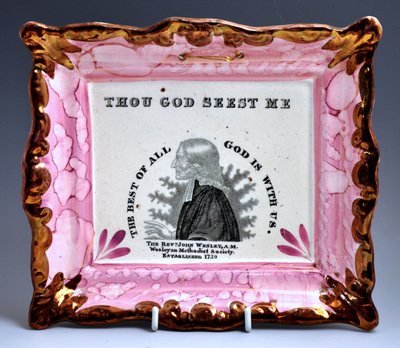

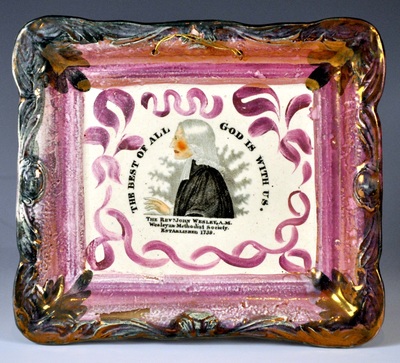

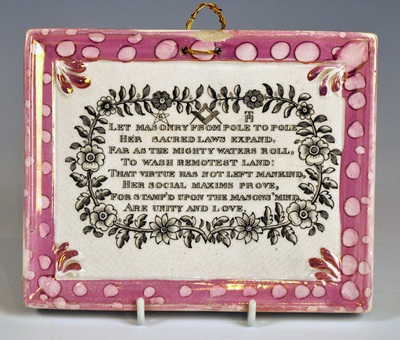

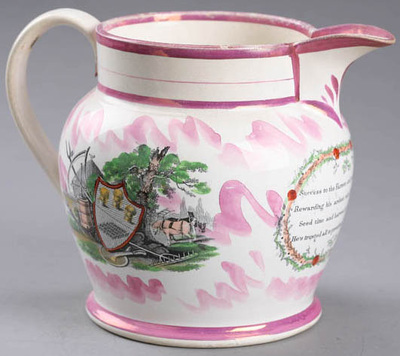

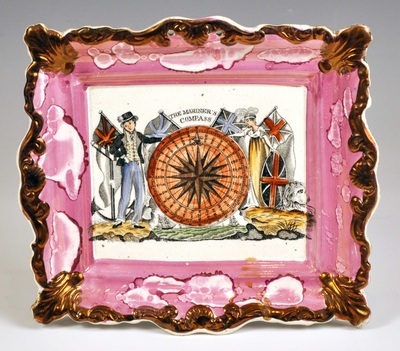

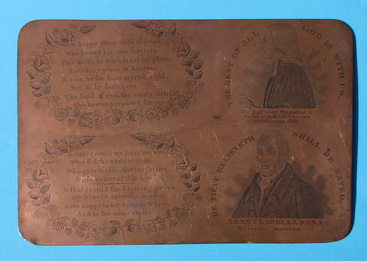

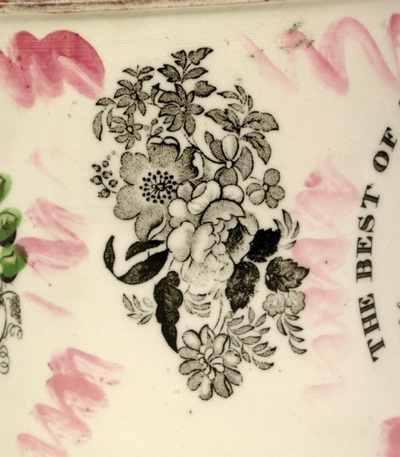

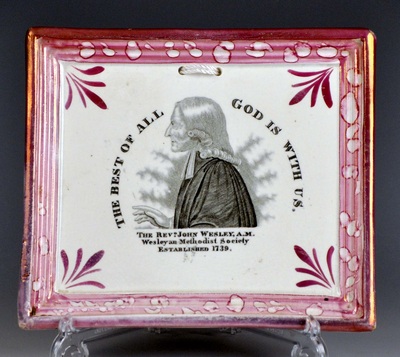

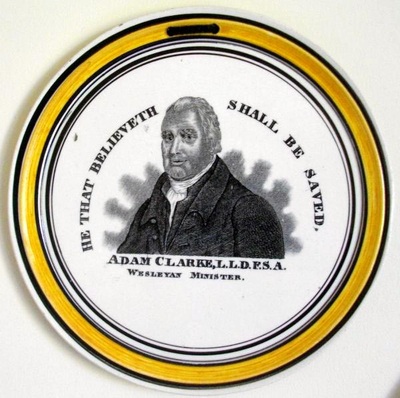

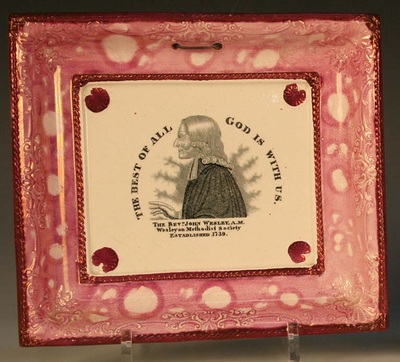

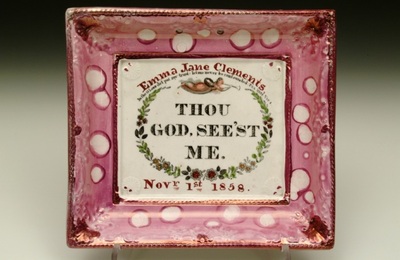

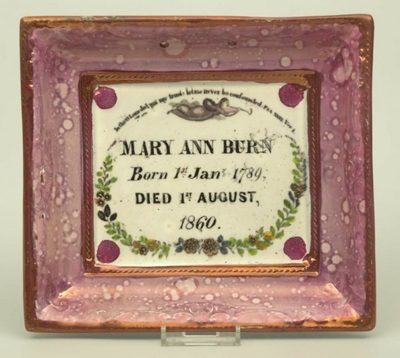

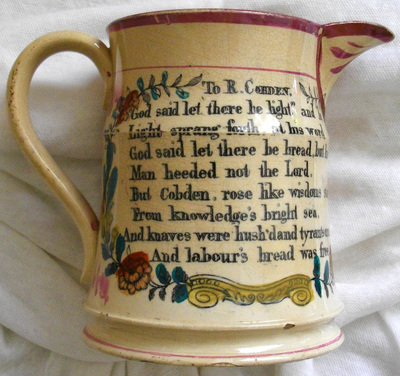

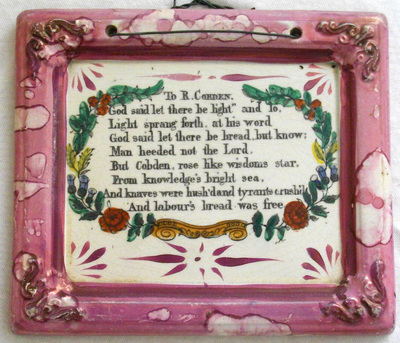

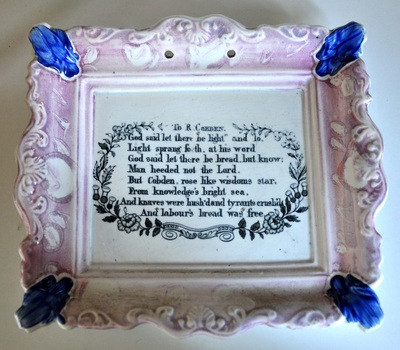

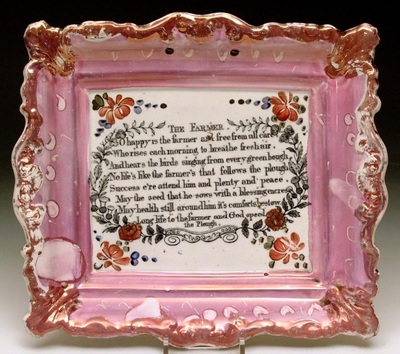

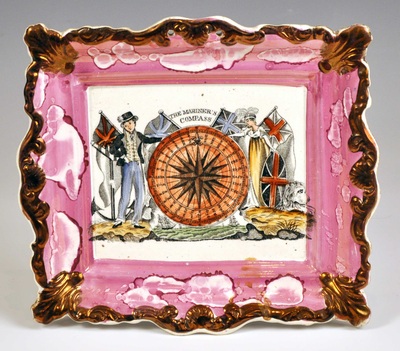

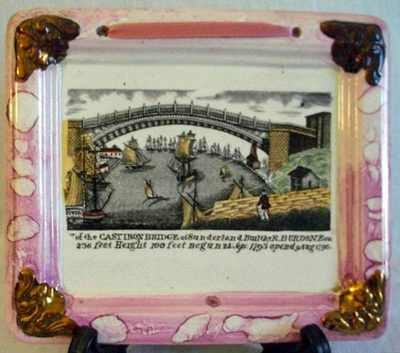

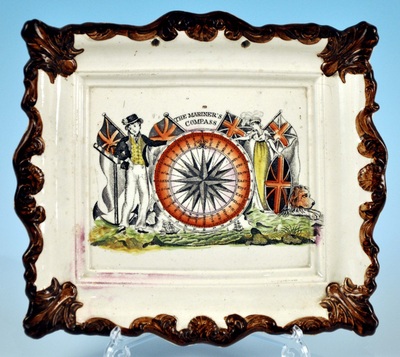

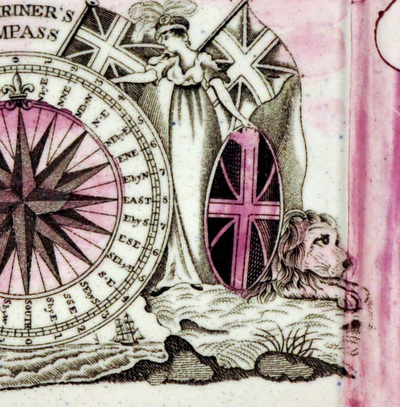

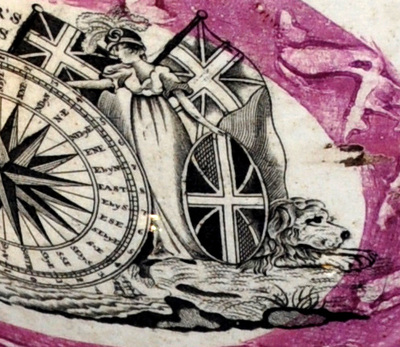

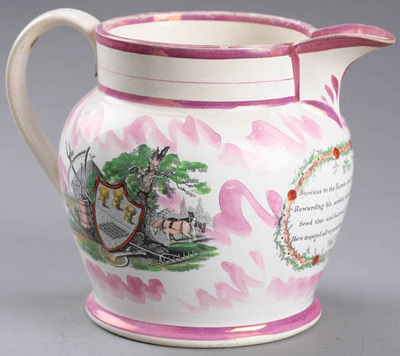

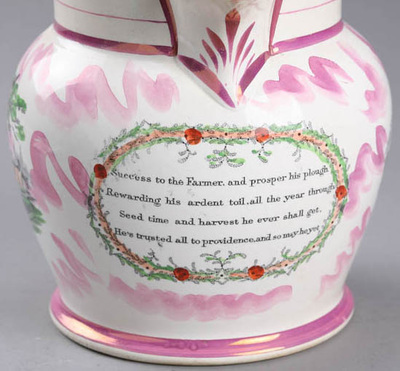

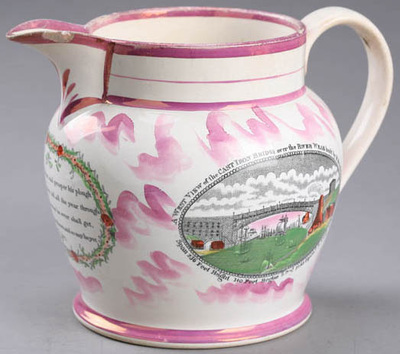

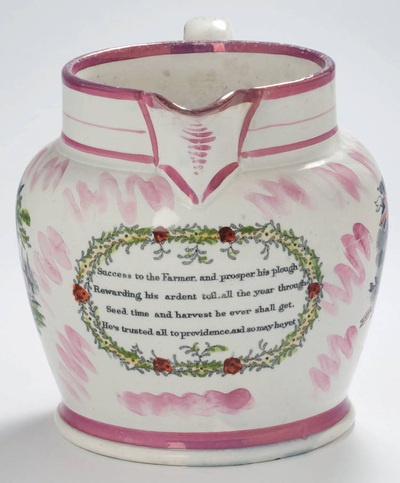

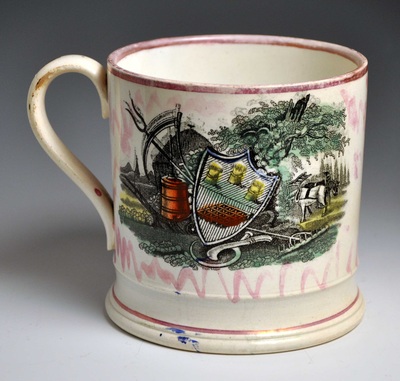

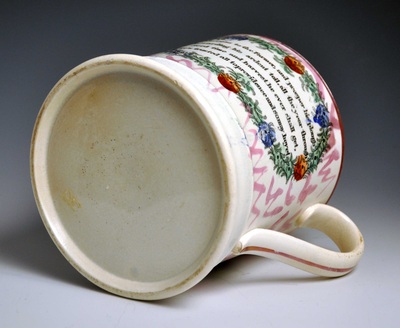

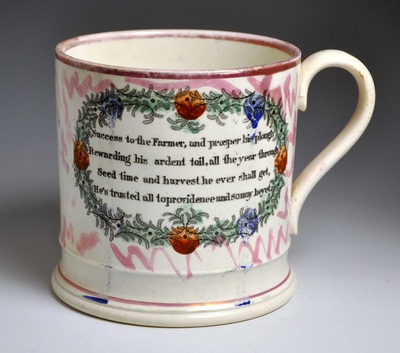

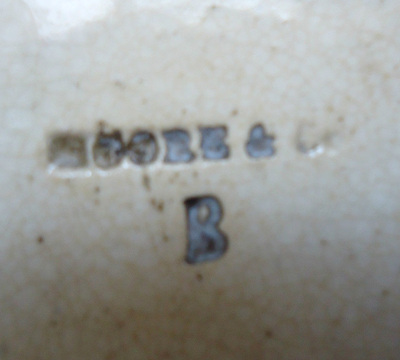

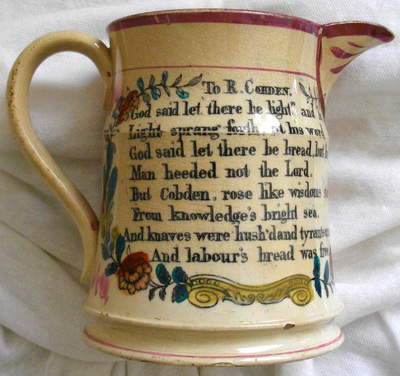

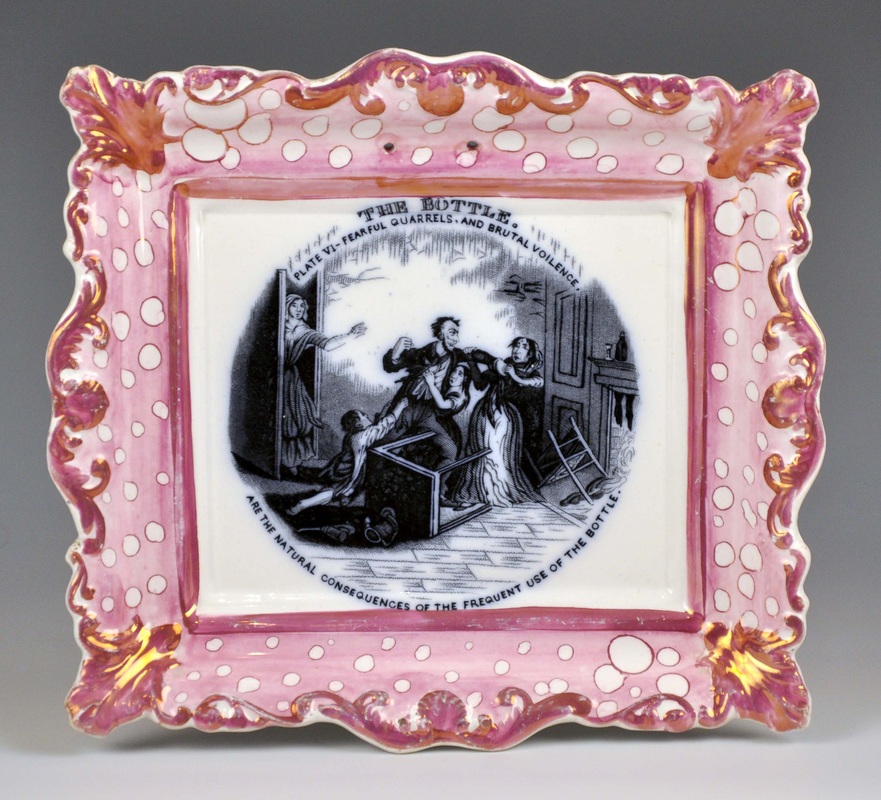

There are fewer Scott transfers that don't appear on Moore items than I first thought when I started this blog a few years ago. For instance, the two Moore bowls at the end of my last post have transfers like 'A Frigate in Full Sail' and 'The Pensioners Yarn', which I previously thought belonged exclusively to Scott, because they've not yet been recorded on Moore plaques. But if we look back to the pre-1860 period, there are two distinct groups of Scott-attributed transfers, which don't appear on Moore wares (or at least, not until c1865 and the orange lustre period). What's more, each of those 'Scott' groups has its own associated plaque forms and decoration. There is no cross pollination between the two groups. All of this troubled me. How did the plaque moulds and transfer plates of these two Scott groups remain so completely apart? The most obvious answer would be that they were separated geographically, and the two groups come from two different potteries. In which case, would the real Anthony Scott please stand up? Alternatively, they could have been separated temporally, and each belong to a different era of Scott production. In that case, the moulds and transfer plates of one of the groups must have lain dormant in an attic somewhere for a period. What I mean will become clearer if you read on. Scott group 1Some of the transfer plates in this group date from as early as the 1830s. Very unusually, two still exist (now in the New Room, John Wesley's Chapel, Bristol); one of which is shown below. These images of John Wesley, and its pair, Adam Clarke, along with the Charles Wesley verses appear frequently on typical Scott items, like the cup below (click on the images to enlarge). They appear on small round and rectangular plaques from about 1832 onwards (the year of Clark's death). A plaque apparently from the same rectangular mould, and with the date inscription '1838' came up in an auction at Dreweatt Neate a few years ago (see below). But these transfers never appear on the heavy brown-bordered plaques commonly associated with Scott from the 1860s. And they never appear on pink-lustre Moore plaques. But interestingly, the Wesley transfer and the common religious verses (Sunderland plate 1) appear on the finely moulded plaques below. Verses on these plaques have been recorded with hand-painted inscriptions and the dates 1858, and 1860. So there is a 20-year gap between the plaque forms above and below, during which the transfer plates appear to have been out of service. Other transfers that appear on these plaques are the Farmers' Arms, the Sailor's Return, maritime and farming verses (see Dick Henrywood, Poor Man's Pictures, Part II, for a 'Success to the Farmer' verse), West View of the Cast Iron Bridge over the Wear, and New Bridge over the River Wear. The New Bridge opened in 1859, but this bridge transfer originated in the Garrison Pottery and first appeared on Dixon items. The transfer plate was likely bought by Scott when the Garrison Pottery closed in 1865, which helps us date the last two plaques below. So, at the same time Scott is said to have mass-produced the brown-bordered plaques, they were also, apparently, making the finely potted and high-quality items below. Religious verses (Prepare to Meet Thy God, etc) on these plaques are common. John Wesley, the Farmers' Arms and New Bridge plaques are rarer (I've seen a handful in the last 15 years). But the others are so rare I've only ever seen one of each. The fine potting and decoration of plaques from this mould didn't last. By the 1870s the potting had become clunky, and the transfers less carefully applied (see left below). In this later period, transfers from the brown-bordered plaques begin to make it onto this plaque form. The square plaque form below, in the pink-lustre period (c1860s), appears to have been used only with the common verse transfers in this group (Sunderland plate 1), although there may be a John Wesley or an Adam Clark out there somewhere. By the orange lustre period (c1870s), transfers that appear on brown-bordered plaques make it onto this form (see top centre). The orange lustre is often degraded, with deterioration of the detail of the moulding, and the plaques are more heavily potted. The similarly moulded rectangular form with rounded corners is always heavily potted (even the pink-lustre versions). It is found with the Scott group 1 transfers, and with the ship transfers that originated at Moore's. The quality of the Wesley plaque below is so poor that it likely post-dates the Scott period (ie post 1897), and was made when the moulds and transfer plates moved to Ball's Deptford Pottery. Scott group 2The Scott group 2 transfers appear to originate in the 1840s. Richard Cobden and verses relating to him and farming appear on the two plaque forms below. Cobden was a hugely popular figure in 1846 because he'd been instrumental in repealing the corn laws, and lowering the price of bread. But Cobden was a pacifist and opposed action in the Crimea (a popular war) so by the mid 1850s he'd fallen from public favour. This allows us to fairly accurately date these plaque forms. They are more heavily potted than the plaques with the Moore impress from this period. Although the transfer never appears on plaques with Moore marks or with typical Moore decoration, it does appear on other later items. The jug below, for instance, has zig-zag lustre decoration (like the letter 'M') often associated with Moore. Previously I've mused over the suggestion that this jug was made by Carr. But I now think that unlikely. The decoration of the Cobden verse on the jug is very similar to that on the 'Scott' plaques. The Cobden verse also appears on plaques with blue corners, as does a verse titled 'The Farmer'. The flower decoration on the bottom left plaque is the same as that found on verse plaques attributed to Scott (Sunderland plate 3). If the blue corners look familiar, hold that thought. They also appear on Scott-attributed 'May Peace and Plenty' plaques. A feature of some of the plaques in this group is a copper-lustre border, carefully painted to the outside edge (see below centre). These plaques are more finely potted than the later Scott-attributed plaques with brown borders, on which this transfer also commonly appears. (Cobden and his related verses never make it onto the brown-bordered plaques, probably because of his wain in popularity as discussed above.) Other transfers found on these 'group 2' plaque forms are the Mariner's Compass, Mariners' Arms, and the 'Cast Iron Bridge' over the River Wear. Now here's what troubled me. The reason these plaques are attributed to Scott is solely that the transfers also appear on the typical 'Scott' brown-bordered plaques (like the one centre below). Unlike the 'group 1' transfers, I'm not yet aware of them appearing on early Scott items. So could this limited group of transfer plates have been acquired from another pottery, and the plaques above been made somewhere else? There are many variations of the Mariners' Arms transfer, used by several potteries, so that's not much help. The Mariner's Compass, on the other hand, appears less frequently. I remembered it on a Seaham jug in the Sunderland Museum, but looking at the details below, the third (from the jug) is clearly from a different transfer plate. Click on the images to enlarge. Could all of these group 2 items have been made by Moore, as the Cobden jug might suggest? Potentially they could, but the same issues would still need to be addressed. Why was this group of transfers and plaque moulds kept so completely distinct from Moore's other items? Why do they never appear with Moore impressed marks, during a period when Moore put their mark on everything else? And why is the decoration so different from Moore's other items of the period? All things considered, they do still seem more likely to be Scott, made during the 20-year period between the early group 1 plaques, and the later group 1 plaques. What else was Scott doing during that time? Now here's one more puzzle. The ships that appear on brown-bordered plaques (bottom row below) frequently appear on orange-lustre plaques, along with transfers from 'group 1' above. And yet the transfers of 'group 2' (top row below), which also appear on brown-bordered plaques, have never been recorded with orange lustre. So even amongst the brown-bordered plaques, there appears to be a division of two groups. Could the brown bordered plaques have been made by two different potteries (Scott and Moore)? The main argument against this is the homogeneity of decoration and quality of lustre of the plaques below. Finally, here's another category of brown-bordered plaques, with transfers that neither appear on early Moore plaques, nor late orange-lustre 'Scott' plaques. I'm sure there are more! P.S.Below are two jugs, which further tie the 'group 1' transfers to Scott. The decoration is typical of that pottery, with soft curvy squiggles, and like the plaques, the jugs are of a high quality. On the first jug, the third transfer is of the old bridge, so it could pre-date 1859. The Crimean transfer on the second jug might also suggest an 1850s' date, although I suspect this transfer was used into the 1860s and perhaps beyond. Now compare the quality with the Moore items below, which have the same transfers (the mug is unmarked and attributed to Moore on the basis of the zig-zag decoration). It seems possible that the transfer plates started off at Scott, and moved to Moore at a later date. This might be borne out by letter 'B' under the impress on the bowl. A similar lettered impress appears on an orange ship plaque from post 1870. However, as Norman Lowe has suggested, it is also possible that by this period both potteries were sending wares to Sheepfolds Warehouse to be decorated. I think something similar can be said of the Cobden jug, with its clumsy decoration. Ian Holmes has suggested that the Cobden transfer might have been revived in 1865, to commemorate his death. Ian Sharp has a similar jug for sale on his website, which he also attributes to Moore. It has the New Bridge transfer, acquired from the Garrison Pottery in 1865. So the transfers from group 1 (bottom row) finally come together with those from group 2 (top row) on Moore-attributed items. Although the relationship between the two potteries is complex, I do believe that one day somebody will be able to unpick it. As always, if you have items or information that might help, please get in touch.

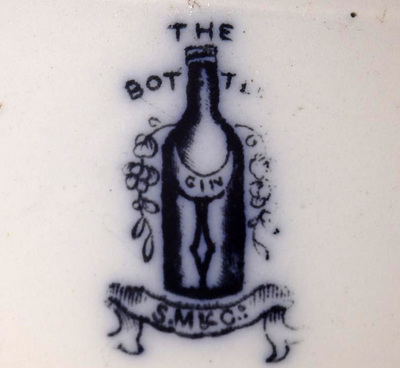

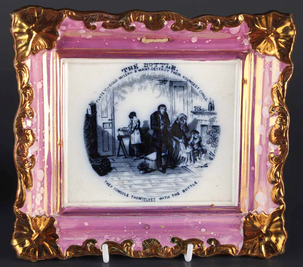

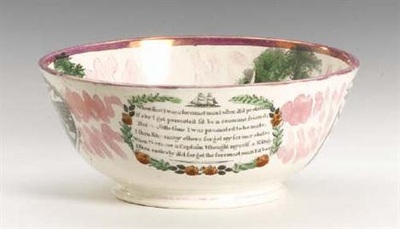

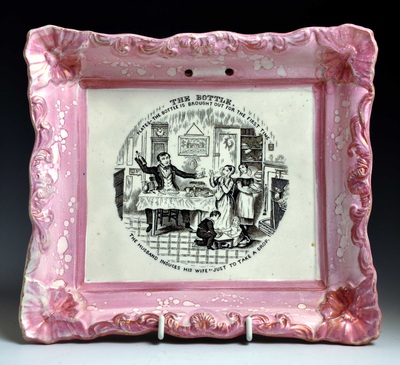

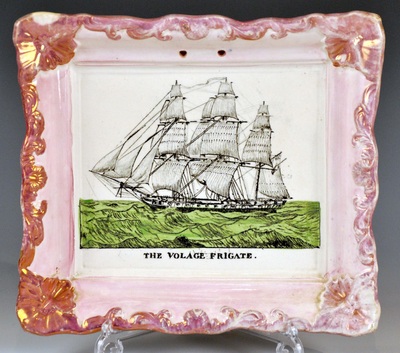

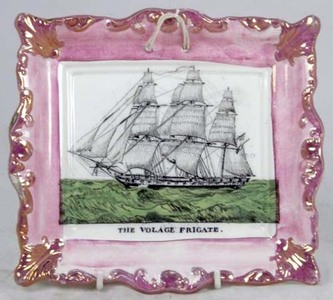

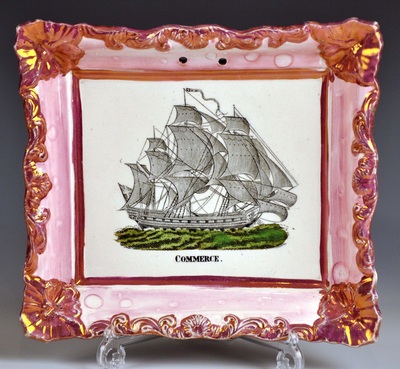

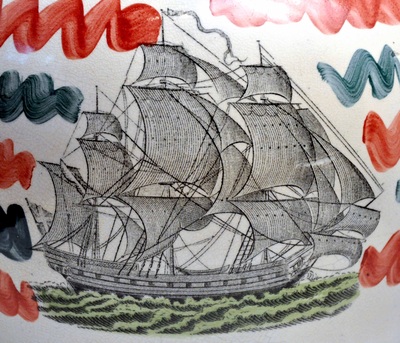

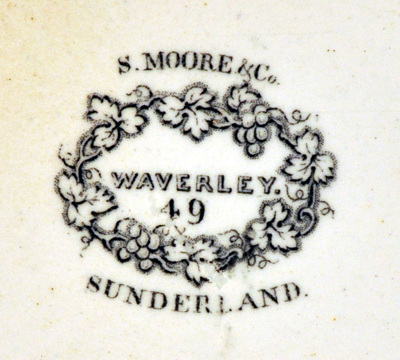

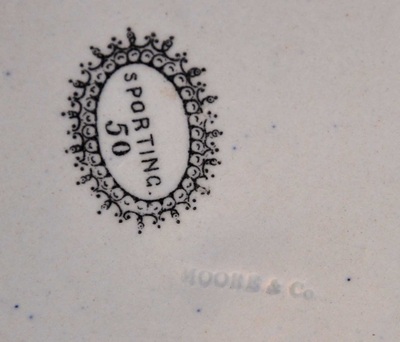

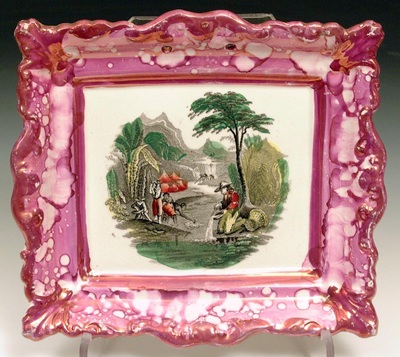

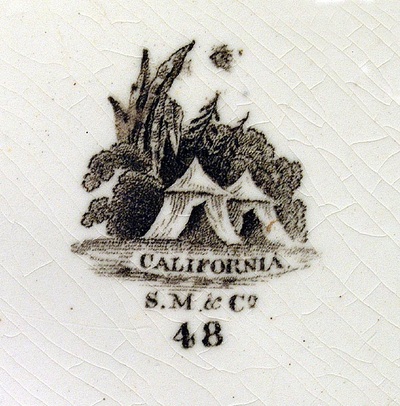

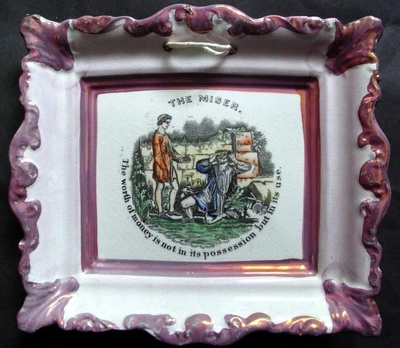

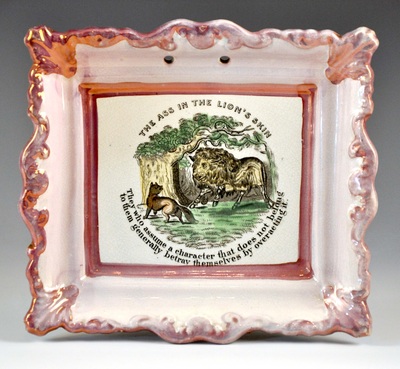

Of all the North East potteries producing transfer-printed plaques, Moore & Co's Wear Pottery in Southwick is hard to beat. Which other pottery could match the quality of the plaque below (the best of its kind I've ever seen)? For lightly potted plaque forms, quality of decoration, and the sheer variety of transfers - series like The Bottle and Aesop's Fables - Moore takes, in my view, the gold medal. I have written before about transfers which Moore shared with the neighbouring Sunderland pottery Scott. But Moore produced many transfers that never appear on Scott wares. My guess is that these were produced earlier, in the 1840-55 period. Here's a short survey of those which appear on plaques. Cruickshank engraved The Bottle series in 1847. It's perhaps a surprise that the circular plaque on the left was produced that late, as it's a form I'd associate with the previous decade (if you are the owner, I would love better photos). The elaborate printed mark is another detail that few North Eastern potteries troubled with. Incidentally, Moore used the 'S. M & Co' mark, long after Samuel Moore's death in 1844. Although many of the ship transfers used by Moore also appear on Scott items, the transfers below appear to be exceptions. HMS Volage (images 1 & 2 below) served in the first Opium War of 1839–42, before becoming a survey ship in 1847. The Steamship Trident (images 4 & 5) was commemorated in an engraving in 1842. This would fit with an 1840s' date for the plaques below, which mostly have Moore & Co impressed marks. Below is another transfer of a ship, which appears on plaques with different titles (Commerce, Union, Resolution, Victor, Eclipse). The ship names would have been engraved on separate transfer plates - another Moore touch. The ship transfer appears untitled on jugs (see below) with distinctive decoration. One came up at Anderson & Garland recently with a dated inscription, 1838 (bottom right). This ship transfer nearly always appears on rectangular plaques with 'scalloped corners' (Ian Sharp calls them 'butterfly corners', which is perhaps better) as below. The circular plaque is the only one of its kind that I've seen with this ship transfer. Transfers titled 'Waverley' (images 1 to 6 below) and 'Chantry' (images 6 to 9) appear on unusually large rectangular plaques, which Baker dates as 1840s. They also appear on the more usual plaque forms with pink lustre. These transfers were reproduced in large numbers, relative to most of the others in this post, but to my knowledge never appear on Scott items. The next Moore series, 'Sporting', are interesting from the point of view of dating. The first three plaques below have the printed mark 'Sporting'. However, by the time the last two were produced, a pattern number '50' had been added to the printed mark. The first three plaques were likely made in the 1840s, and the last two perhaps into the 1850s. The marks belong to the plaques to their left. Note that the third appears in conjunction with the impressed mark 'Moore & Co'. Moore produced several other landscapes. The first three have the Moore & Co impress, and are typically decorated with an inner and outer frame of dark lustre. The second row have the printed mark 'Cuyp' after the Dutch painter of cows. The last plaque commemorates the 'California' gold rush of 1848. Moore produced a series of transfers of Aesop's fables, but they so rarely appear on plaques the two below are the only ones I've ever seen. They both have three marks. The left mark identifies that the designs were registered in 1853. You can see more of the series on a bowl here. To go out with a bang, here are two Moore portraits. They could be a little later than the plaques above, as the centenary of Robert Burns' birth was in 1859, and the tricentenary of William Shakespeare's birth in 1864. The transfers are very rare, but to date I haven't seen them on Scott items. So why does dating them matter? Well, the copper transfer plates from which the transfers were printed could only be in one place at a time. So I've been wondering where the transfers shared by Scott and Moore originated. It seems almost certain that it was Moore (with their track record of design innovation) who had the plates engraved. The Moore plaque below left is entirely in keeping in style with the Crimean period of c1855. What's more, the plaque has the Moore & Co impress, just like the plaques above. The confusion arises because Scott is attributed with making, I'm guessing sometime after 1860, many, many more plaques with this transfer than Moore ever did (see below right). Incidentally, since writing the blog post in 2011, I've seen several bowls with the ship transfers and a Moore impress. One came up at Bonhams recently with a hand-painted date, 1859. I've included another below. However, it has a letter under the impress, so is likely later. My guess is that there was no overlap of production of the two plaque types above. Sometime around 1860 either:

P.S. There are likely more plaques with mid-century Moore transfers to be discovered. For instance, I know of one with a Highland family, which I haven't yet managed to photograph. |

AuthorStephen Smith lives in London, and is always happy to hear from other collectors. If you have an interesting collection of plaques, and are based in the UK, he will photograph them for you. Free advice given regarding selling and dispersal of a collection, or to those wishing to start one. Just get in touch... Archives

February 2022

AcknowledgementsThis website is indebted to collectors, dealers and enthusiasts who have shared their knowledge or photos. In particular: Ian Holmes, Stephen Duckworth, Dick Henrywood, Norman Lowe, Keith Lovell, Donald H Ryan, Harold Crowder, Jack and Joyce Cockerill, Myrna Schkolne, Elinor Penna, Ian Sharp, Shauna Gregg at the Sunderland Museum, Keith Bell, Martyn Edgell, and Liz Denton.

|